An autistic person falls down the rabbit hole the day they are born into the neurotypical world.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a children’s novel published in 1865. A young girl, Alice, falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of paradoxes and talking animals.

Alice in Wonderland is a perfect allegory of autism. Alice’s struggles in the bizarre reality of Wonderland are painfully relatable for an autistic person.

Life as an autistic Alice in Wonderland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland represents the literary nonsense genre. It creates a balance of meaning and lack of meaning. Logical elements balance the ones that don’t make sense.

Wonderland has its own rules that are different from those in our world.

For an autistic person, it’s difficult to understand the rules of the neurotypical world. We try to play by the rules, but they are so absurd that we fail.

An awkward conversation with the Caterpillar

Alice does her best to be polite to the animals she meets in Wonderland. Yet she always seems to say something wrong and upsets these creatures.

Alice’s awkward conversation with the Caterpillar is a fitting example of her communication issues in Wonderland.

This was not an encouraging opening for a conversation. Alice replied, rather shyly, “I — I hardly know, sir, just at present — at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

“What do you mean by that?” said the Caterpillar sternly. “Explain yourself!”

“I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, sir,” said Alice, “because I’m not myself, you see.”

“I don’t see,” said the Caterpillar.

Alice and the Caterpillar view things differently. That’s why they have trouble understanding each other.

That is often the case when both an autistic person and a neurotypical person attempt to communicate with each other. We have different communication styles, which creates difficulties.

However, society blames autistic people for having communication issues. Neurotypical people expect us to change our communication style to fit the neurotypical norm.

It doesn’t work like that. Communication is a two-way street. The Caterpillar should make an effort and try to understand Alice. Neurotypical people should also meet autistic people halfway and try to understand our way of thinking.

A mad tea party

In Alice in Wonderland, Alice joins a mad tea party with the Hatter, the March Hare, and the Dormouse.

When Alice approaches the table, the Hatter and the March Hare make it clear that they don’t want her at their table:

The table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it:

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

“No room! No room!” they cried out when they saw Alice coming.

The scene is like a school cafeteria. Many autistic adults have painful memories of not being wanted at the cool kids’ table.

The tea party doesn’t get any better when Alice sits down. The Hatter and the March Hare make mean comments to Alice. When they’re not being rude, they talk about such strange matters that Alice has trouble understanding them:

Alice felt dreadfully puzzled. The Hatter’s remark seemed to her to have no sort of meaning in it, and yet it was certainly English.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

For an autistic person, any social event can be a mad tea party.

A simple question such as “How are you?” may feel like a riddle you can’t solve.

What does the other person expect me to say? “Good, how are you?” Or should I say how I actually feel?

“How was your weekend?”

I think I’ll leave this tea party, thank you.

“Off with his head!”

“Off with his head!” The Queen of Hearts in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland exclaims when someone displeases her in any way at all.

For an autistic person, dealing with real-life Queens of Hearts is hard. Autistic people often have a strong sense of justice. It’s difficult for us to deal with injustice when we witness it.

Often autistic people are the victims of injustice. We’re judged unfairly and excluded from social activities because of our differences.

Croquet with flamingos

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice joins a chaotic croquet game with the Queen and her court. Flamingos are used as mallets and hedgehogs as balls.

Alice soon came to the conclusion that it was a very difficult game indeed.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

The players all played at once without waiting for turns, quarreling all the while, and fighting for the hedgehogs;

When I was a child and attended a gym class at school, I felt like Alice trying to play croquet with flamingos and hedgehogs.

There was this stupid system; two students got to pick members for their teams. I was always the last one who got chosen. That alone ruined my self-esteem.

I hated playing ball games. I was always afraid the ball would hit me in the face. I had trouble catching and throwing the ball.

Difficulty in catching a ball is common in autistic children. Of course, I didn’t know I was autistic until later in life.

Mocked by the Mock Turtle

Many animals in Wonderland are rude to Alice and make fun of her.

Alice pities the Mock Turtle for his sadness. Despite Alice’s empathy, the Mock Turtle and the Gryphon humiliate her:

“We called him Tortoise because he taught us,” said the Mock Turtle angrily; “really you are very dull!”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself for asking such a simple question,” added the Gryphon; and then they both sat silent and looked at poor Alice, who felt ready to sink into the earth.

Most autistic people know what it’s like to be bullied. It’s easy for me to relate to Alice’s ordeals.

Despite the hardships, Alice doesn’t lose her spirit in Wonderland. The two-faced creatures can’t break her down.

It’s both empowering and liberating how Alice stands up for herself in the court:

“Hold your tongue!” said the Queen, turning purple.

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

“I won’t!” said Alice.

“Off with her head!” the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

“Who cares for you?” said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”

I wish I could have told my bullies they were “nothing but a pack of cards”.

The power of literature is such that in my mind, I almost can.

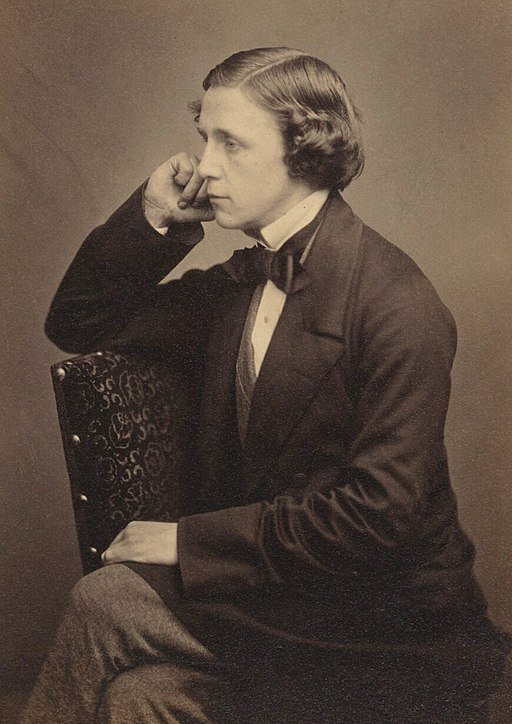

Was Lewis Carroll autistic?

It is a common belief that Lewis Carroll (1832–1898, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson by his real name) was autistic. Of course, he couldn’t get a diagnosis; Carroll lived and died before the autism diagnosis existed.

Lewis Carroll had difficulties with social interaction. He got along better with children than grown-ups. Carroll struggled with small talk and was often silent in adult company. He disliked groups of people and preferred individuals.

Carroll “showed a lack of appreciation of social cues and socially inappropriate behavior”.

Lewis Carroll had a fixation on his routines and experienced sensory hypersensitivity.

Carroll was obsessed with his interests; writing, mathematics, and photography.

Lewis Carroll had so many typical autistic traits that he probably was autistic. Maybe Carroll created Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to process his feelings of not fitting in.

Literature helps me cope with my life as an autistic Alice in Wonderland

Lewis Carroll’s novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is an allegory of life as an autistic person in the neurotypical world.

Alice finds herself in a strange, chaotic world where nothing seems logical.

Shrinking and growing multiple times, Alice doesn’t fit in her environment in Wonderland, literally.

Alice tries to communicate with the creatures she meets, but they misunderstand everything she says.

Like Alice in Wonderland, an autistic person faces bizarre situations in daily life. We try to function in a strange world that wasn’t made for us.

Lewis Carroll himself had many autistic traits. He probably was autistic. Alice in Wonderland may have helped him process his feelings of not belonging.

Now, centuries later, his beloved children’s book helps other outsiders to understand their experiences.

Finding a literary allegory helps me cope with my life as an autistic Alice in Wonderland.

The author has a Master’s degree in comparative literature. She has been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome and ADHD.

More posts you might like:

Brilliant!! I’ve often felt my autistic son must feel like he’s in a foreign land where he doesn’t know the language. The Alice allegory is so good.

Thank you, happy to hear this post resonated with you.

Kirsty, it makes sense what you say

i’ve just been watching the [brilliant] jonathan miller 1966 bbc tv movie of alice in wonderland – encapsulates my own experience in childhood and teens as an undiagnosed autistic girl, solemn and baffled, surrounded by cartoonish people playing idiotic games and making incomprehensible noise, feeling so alien, wondering ‘who am i and what’s going on?’

people only make more sense to me now i’ve spent decades studying psychology, sociology, anthropology etc 😉

Hi, Elizabeth! Thank you for your comment. The way you describe your life as an undiagnosed autistic girl also sums up my childhood and teenage experiences.